A week before my marathon debut in Mississauga (read the gripping three part series here (1), here (2), and here (3)). I went to Toronto to do a level one Chi Running workshop with John and Hyongok, who are certified instructors from Montreal. I had originally considered going to Ohio to do one with Danny Dreyer, author of the book and inventor of the style. But when Sam pointed out I could do a workshop in Toronto, which is so much closer to home, that seemed like a good option and I took it.

A week before my marathon debut in Mississauga (read the gripping three part series here (1), here (2), and here (3)). I went to Toronto to do a level one Chi Running workshop with John and Hyongok, who are certified instructors from Montreal. I had originally considered going to Ohio to do one with Danny Dreyer, author of the book and inventor of the style. But when Sam pointed out I could do a workshop in Toronto, which is so much closer to home, that seemed like a good option and I took it.

I successfully tempted two friends into spending the last Saturday morning of April with me at the half-day workshop: Anita (who I train with a lot and I ran the Scotiabank Waterfront Half with, and who’s also signed up for the Niagara Women’s Half and the Kincardine Women’s Triathlon) and Violetta (a great friend who lives in another town and who I’ve never run with before).

Anita and I stayed over in the same hotel the night before and met in the lobby at 8:15 to run the 3K to the workshop location in a school gym. It was a beautiful day, if a little on the cool side, and the workshop took place mostly inside.

There were ten or so students and the two instructors–John, a proper British man and Hyongok, a no-nonsense Asian woman with few qualms about pointing out what might be wrong with the way people run. She did most of the hands-on instruction, with John stepping in once in awhile or whispering something to her that she may have overlooked.

Hyongok wore extremely minimalist shoes with no support and hardly anything to them. When she demonstrated running, she almost appeared to float, so lightly did her feet touch the ground. Violette whispered to me, “yes but she’s so tiny!” As if reading our minds, John pointed out that the lightness of Hyongok’s step “has nothing to do with her weight.”

The were quick to point out that most people have too much going on with their footwear and often have their laces tied too tightly. I like foot support, but I also like loose laces because otherwise my feet fall asleep.

We went around the room doing introductions, each explaining where she or he was in her running “journey.” Almost everyone had been injured or was there to avoid injury. Chi Running purports to offer a pain-free technique that will enable people to run without injury for the rest of their lives.

John the gave an overview of what would be the three focal points of the day: the column (body position), the foot placement, and the lean. Above all, he said, running should be relaxing and relaxed. You should feel like you can run forever. This strikes me as an awfully optimistic view of running. I love it, yes I do, but I rarely (if ever) feel like I can run forever.

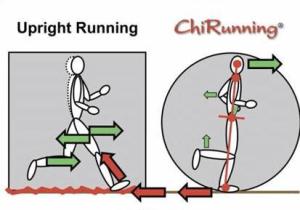

The column is the name for the postural alignment recommended for chi running. In this posture, your upper body is balanced over and supported by your lower body in a straight line. Your hips aren’t pressed forward out of alignment, but rather are stacked over your legs so that when you look down you can see your shoe laces.

Here’s description from an article on Chi Running by ultra runner, Nick Mead, after he did a chi running workshop:

Chi running sets out four steps to a good posture:

1) Stand with your feet pointing straight ahead, a hip-width apart.

2) Lengthen your spine so you’re feeling tall – raising your hands in the air above your head and allowing them to fall back can help, especially for corrections as you run.

3) Level your pelvis, which is generally tilted forwards. To do this, place one hand face down on your tummy with the thumb in your belly button and the other hand face up on your back directly opposite, then gently tip your pelvis back to a level position. You should feel your core muscles engage – but don’t go so far that your core becomes tense or that your glutes tighten.

4) Place both thumbs on the prominent front hip bone at the top of your legs and pivot forwards from there until you are balanced over your centre of gravity.

We spent a lot of time getting settled into this posture, looking down at our shoe laces. Westerners tend to hang out in the lower backs when they’re standing, hips protruding forward. So it’s not a natural posture for everyone, though people who have practiced yoga (tadasana or mountain pose) or tai chi (on which chi running principles are based) may be more familiar with the instructions. Some people struggled with the very basics, unable to stand with their feet pointing straight ahead.

As is the case with these types of things, a lot of the workshop involved attempts to explain what a physical posture or movement “feels like” and then asking us if we feel it. I realize that there’s often no other way, but it’s not always possible to tell if you “feel it.” It’s also not clear to me that everyone feels “it” the same way. I’m fairly naturally given to walking and running with my feet pointing straight ahead rather than outwards or inwards, but not everyone is like that. It seemed to me that some of the workshop attendees might have needed surgical re-alignment to get their feet to point straight ahead.

We worked in pairs with the column, pushing down on each other’s shoulders when properly stacked and when not. With the posture in place, you didn’t budge when your friend pushed down squarely on your shoulders. But when we hung into our low back and pressed our hips forward, pushing down on our shoulders made us wobbly and unstable.

Foot placement in chi running is all about the midfoot strike. They didn’t call it this exactly. They spent a lot of time talking about the outer edge of the foot and trying to help us gain an awareness of its connection to the ground. Most people don’t connect all areas of the tripod of their foot to the ground. And runners who connect with the heel first are just asking for trouble.

The foot placement is the main thing I internalized from working with the book. I’d been experiencing shin pain and I’d read that it was the result of heel striking. As soon as I started to work with a midfoot strike, the pain evaporated.

The next thing we worked on was the lean. The whole idea behind chi running is that you work with gravity not effort. Doesn’t that sound so easy? We don’t even have to fight against gravity, we just go with it. That’s where the lean comes in. You lean forward with the column all nicely aligned. At a certain point–gravity is so amazing!–you will fall down if you don’t put your foot forward.

The next thing we worked on was the lean. The whole idea behind chi running is that you work with gravity not effort. Doesn’t that sound so easy? We don’t even have to fight against gravity, we just go with it. That’s where the lean comes in. You lean forward with the column all nicely aligned. At a certain point–gravity is so amazing!–you will fall down if you don’t put your foot forward.

We stood in front of the wall leaning forward and pushing ourselves off for quite awhile to try to get the feel of the lean.

Another lean drill we did was to lean until we had to put a foot forward, then push back into the original stance and do it again.

The lean is not the same as bending from the waist or hips. Not at all. The column stays straight.

When the one foot goes forward, you don’t push off of it for momentum. You keep leaning and peel that foot off the ground (I like the book’s description “like peeling a self-adhesive stamp off of its backing”) while placing the other down.

The other thing we did was to run with a very small resistance band loop around our feet to teach us to take very short steps. According to Hyongok, people almost universally overstride. But in chi running you don’t want your foot to go forward of your knee. The stride goes to the rear.

The resistance band exercise shocked me because of just how short the stride was. I always thought I had a short-ish stride. When I see people running in the park, they always seem to have gazelle-like legs taking long, powerful, graceful strides forward. But with the band around my ankles I felt as if I could hardly take a step.

The short stride goes with a quick recommended cadence of 180 steps per minute. Hyongok and John talked about different settings for the running metronome (every stride, every other stride, or every third stride). They favor every third step because 180 beats of the metronome per minute is just a bit too much noise. Every second step makes you naturally put emphasis on the same foot all the time. Every third is just right. Their metronome didn’t want to work that day so Hyongok mimicked the beats with clapping, explaining that she had internalized the 180 steps per minute.

Here’s what I have to say about that: it’s fast. Faster than I’m used to. And it requires shorter steps. They explained that regardless of speed, you keep the cadence at 180. When you want to go faster, lean more sharply. The stride will lengthen itself. Here’s a great little post by Danny Dreyer about short stride and fast cadence.

At that point I realized I was ravenous and hadn’t brought a single thing to eat. Hyongok did a demo with a banana, something to do with the way it peeled. I just wanted to eat the banana. Then John said that if we practiced up and down the gym with the resistance band a few more times, we could have a snack. But the practice seemed to go on and on. So much so that Anita actually asked at one point, with a hint of desperation in her tone, “when do we get our snack?”

Since I was the first to try the resistance band thing, I made an executive decision that I would be the first to take a snack: chocolate energy bars — not vegan but delicious — and a banana.

We also learned about arms swinging to the back instead of the front and never crossing the body. For some of these things, I’m not sure if the movement is actually like that or if it’s just something we’re supposed to visualize. For example, in yoga you sometimes get instructions to do things that are impossible, like reach for the ceiling or the opposite wall. You’re never going to get there, but by visualizing that you get where you need to be. I felt a bit like this with the arm instructions. Do they actually swing to the back or is that just what you think about, like a difference in emphasis?

Finally, at the end of the day we went outside and did a few laps around a short track, practicing our “gears.” Gears come from the lean. This is one of the concepts that I’ve never really gotten a good grip on. I lean forward more sharply but I don’t actually feel as if I’m going faster. I’ve got my swimming gears and my biking gears all figured out. But in running, I’m terrible at gears. I just go. And then my pace slows because I get tired.

We took turns running up and back in groups, with the other group providing “critiques.” I got some feedback that I didn’t fully understand, something about my legs swinging up too far behind me (which, frankly, I have no sense of at all — when I run I often feel as if I’m hardly even picking up my feet).

By then, almost four hours into with just ten or so minutes to go, my feet felt really tired, the way they might if you spent a lot of time standing in one place, which we kind of had. But we still hadn’t run up and down hills, so we proceeded to the parking garage ramp.

There, we ran down — short steps, minimal lean (so as not to do a face plant), arms swinging to the back. Then we ran up — shorts steps, forward lean, arms punching up (like an upper cut), and it should feel “effortless, like you’re not going up a hill at all.” I’ve been practicing that one on hills ever since and I’m not convinced that it feels as if I’m running on a flat. Maybe it’s easier. I’m just not “feeling it” yet.

We got a hand-out and did a little go-around where everyone said what they got out of the workshop. I can’t even remember what I said.

I was more excited about the workshop than Anita and Violetta because I’ve been dabbling with the principles of chi running for almost three years now, ever since I read the book. See here and here for my previous posts on it. I thought a workshop might help solidify some of the teachings for me. But the “do you feel that?” approach didn’t help me as much as I’d hoped.

Since the workshop, I’ve had some check-ins from John, who is quite willing to answer questions. I told him the truth, which is that I practiced a few things and found them awkward. My lean feels unnatural and when I relax I slow down so much that I’m hardly moving. I tried a cadence metronome app and I had a world of trouble trying to do the three steps per beat thing that they recommended. Then I tried 90 beats per minute, two steps per beat, and got all tangled up and frustrated.

I get that these things take practice, and to be fair, they recommend that you spend a lot of time doing practice drills that are extremely focused on one particular thing at a time. And that you set the Garmin aside, stop worrying about speed for awhile and just get a feel for it. I suppose as with all things, the repeated attention to detail will eventually (we hope) yield an epiphany. I had that experience in yoga once: I’d been in Iyengar classes for about five years when one day I did a make-up class that was a lower level. My shoulder stand was pretty good already, but then the instructor said something that made me experience it in a whole new way. I became stronger and more stable on the spot, my shoulder stand forever improved.

Chi running might be like that. Let’s hope.

To find a Chi Running workshop check out the list of upcoming sessions with certified instructors all over (mostly in the US) here.

I’ve never heard of chi running before this. Definitely going to do a little more research on this! The lean/working with gravity things sounds really interesting. To me it sounds like that method would be really slow, but clearly that isn’t necessarily the case. Hard to image it just reading it though.

It’s not necessarily slow. They have a concept of gears that maps onto the degree of lean. I will be experimenting with that over time and will report back about it. My goal this summer is to shave 7 minutes off my best 10K so we’ll see! Let us know how your own explorations go!

I’m curious to know what you make of the evidence for chi running. There’s been some testing done and it wasn’t found to make a difference in terms of injury prevention. Of course, it helped some people but no more than other methods. I’m always taken aback by the lack of evidence of a wide variety of claims about sports training, not just chi running. Lots of things sound good but then don’t pan out when tested. It’s puzzling. So much sports training advice is of the “it worked for me” variety.

I don’t mind ‘evidence’ of the ‘it worked for me’ variety. Here’s why: we all have different bodies so I like that there are different things to try. It would be absurd to think there is a universal solution (I know you don’t think that). But I agree that proponents of these methods sometimes suggest that their way is a cure-all for any issue or injury. I like to take what’s useful. But i can’t say I’m drinking the chi running kool-aid. The workshop made me less enthusiastic somehow.

Right. I don’t object to the “it worked for me” claims. It’s using those as evidence for the general claim “it works” that bothers me.

Reblogged this on Mama knows best and commented:

I am definitely taking note.

I’m also trying to get all the components of chi running. Learned from a certified teacher, and now I’m practicing. It’s not as simple as it sounds on the video.

You’re right. There’s a lot to keep track of. I think just practicing a couple of the focuses at a time, over time, is the way to go. At least that’s what I’m going to try doing. Good luck with it!

How can you effectively practice what you have not been taught to do not trained to teach? With running most think we all can run. We can. The same as we can all play tennis, golf and piano. Unlike running, these give more instantaneous feedback that we need help…and others see or hear it, too.

Sadly, the content Nick provided is copyrighted source material from Dave Stretanskis Chi Running Simplified. Permission and due credit should appears missing.

The main difference between Chi Running and other methods with the exception of PainFree Method and Good Form is the lack of neuromuscular power (runner generated from engaging muscles) and reliance on natural forces primarily gravity. The primary benefit is less impact being absorbed. Keep in mind “For Every Action There Is An Equal And Opposite Reaction”. Thus, when striking the ground the impact force is returned and whatever energy is not transfered into motion is absorbed in soft tissue and joints. With 1200-1500 strikes each mile and the many miles run….that is a lot of stress. Thus, learning technique is essential for avoiding injury more so than improving speed or distance. In reality, all benefits are realized with good technique vs unavoidable the negatives from not!